Fast Fundraising: the importance of subconscious context

Fundraisers are often concerned with changing hearts and minds. And they're often, especially when prompted by colleagues in advocacy or communications to increase supporters' conscious engagement with the cause. But is this the best or only way to improve pro-social behaviour- whether it's increasing donations, using less plastic, or avoiding bias?

Let’s begin with the science. Fundamental to decision-making is the premise that much of our data processing and decision-making is subconscious and fast. Deciding is so fast, even changing our minds can be difficult. According to some recent research at Johns Hopkins University if we change our minds withing roughly 100 milliseconds of making a decision, we can successfully revise our plans. If we wait more than 200 milliseconds, however, we may be unable to make the desired change. That’s not very long to persuade a donor to look away from our TV ad or crumple our DM pack.

But it’s not just our visual process that’s important. Some senses, for example, are important, especially smell. In a test between two Nike stores, one with a very faint ‘consciously indetectable’ scent and one without, customers were 80% more likely to purchase in the scented store. In another experiment at a petrol station with a mini-mart attached to it, pumping the smell of coffee into the store saw purchases of the drink grow 300%. And if you take the time to wander into the M&M World store in Leicester Square London, you might now notice the smell of chocolate. When it first opened in 2011 it didn’t have the smell and sales were disappointing. They hired a company called ScentAir who specialize in adding signature scents to stores. The managing director of the company, Christopher Pratt, said in an article describing the effect: “It looked like the place should smell of chocolate, it didn’t. It does now.” And sales have moved in response. There was a similar positive response when the National Trust – a UK heritage charity – included a ‘scratch and sniff’ element in an appeal to save a flower meadow.

When you visit a charity website, the conscious brain analyses the message content. (What is the cause I am being asked to support? What do they want me to do – donate, sign a petition or join up?) At the same time the subconscious brain continuously responds to how you respond to the subtle background and peripheral cues. (How do I feel about the colours, images, celebrities involved, and so on).

“I always thought the brain was the most wonderful organ in my body. And then one day it occurred to me, ‘Wait a minute, who’s telling me that’?”

Emo Philips

It’s not all about you either. Your subconscious brain has a mind of its own. Some signals also come from inside us, and we look unconsciously for opportunities to confirm our inner state. When we are in a good mood, we are more likely to tolerate our colleagues and partners and are more likely to donate to charities. These activities become a way to validate or confirm our inner feelings. Let’s look at an example of how this affects our behaviour.

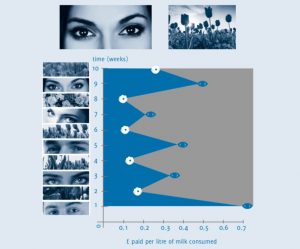

In some companies, and many cost-conscious charities, employees can serve themselves coffee or tea, after putting the relevant amount in an ‘honesty box’, next to the drinks in a kitchen. In an experiment run over ten weeks, researchers at Newcastle University in the UK found that employees were open to subconscious influence based on the picture that they were exposed to. People put more money in the honesty box in the weeks when there was a small, 13cm x 3cm, picture of eyes on the wall of the kitchen, than when it was a similar-sized picture of flowers. Researcher Melissa Bateson reported staff paid 2.73 times more, on average, when the eyes rather than the flower picture was present.

(Over three days at the International Fundraising Congress in Holland we repeated this experiment using soft drinks. Delegates did indeed put more money in the tin provided when overlooked by a picture of eyes that they did with a picture of tulips.)

None of the respondents in either experiment consciously noticed the difference between the two images when they were subsequently questioned. But at some subconscious level the impact of eyes was important.

The original research concluded that eyes act as a symbol of social supervision, suggesting someone is observing you and serving as a cure for pro-social behaviour. Meredith Niles, one of the UK’s leading fundraisers, and an American, points out that “the ‘eye of providence’ or ‘all seeing eye’ (visible on every US dollar bill) represents an omniscient god”. She suggests this image has been used across cultures for many centuries to encourage ‘correct’ behaviour. We may not have always had the science to demonstrate the impact of the eye, but we have had strong intuitions about conscious brain, they activated employees’ social consciousness urging them to do what is socially correct. An excellent illustration of the power of the subconscious brain to process information and take decisions all by itself.

In these, and in many other related experiments, subjects are not only unaware of the cues that drive their behaviour, they refuse to believe that such cues had any influence on their decisions, when told about the experiment. Our hearts ‘dominate’ the minds.

In fact there is real evidence that our expressed attitudes are not a great guide to our behaviour. We don’t always do what we say we would do but will come up with a rationale for why not. Colin Camerer, respected behavioural scientist, has a blunt explanation. ‘The human brain is like a monkey brain with a cortical “press secretary”, who is glib at concocting explanations of behaviour and who privileges deliberative explanations over cruder ones.’ (For more on this you can read: Stop Listening to Your Supporters.)

What is the implication of this subconscious processing for fundraisers and more generally for individuals involved in social change? Websites, mailings, video clips, and other communications media can deliver subtle cues in the background to drive subconscious behaviour while the conscious brain believes it is assessing ‘the cause’ in a rational way. The same ‘eyes’ experiment could encourage employees involved in food preparation to wash their hands after visiting the toilet. Or, as suggested above, you could try putting eyes on or near a static charity collection box in a gallery, shop, hotel reception or pub counter to see if that increases your donations. We have trialled this a number of times in various settings with consistent success. In one specific example eyes placed over a charitable donation box increased donations 48% vs. control with no eyes.

Case Study: Macmillan Cancer Support, a major UK charity, has taken this idea of personal ‘eyes’ interaction to a whole new level. They tested the advert below in a London shopping mall. It uses face recognition technology to change the message displayed according to whether it is mostly men or mostly women walking past. Women get, ‘No Mim Should Face Cancer Alone’ and men, ‘No Dad Should Face Cancer Alone’. Both versions then prompt a £5 text donation. When the immediate audience is less than 60/40 in one gender, a generic ad is shown ‘No One Should Face Cancer Alone’.

The implication of all this? As I began- fundraisers are often concerned with changing hearts and minds. The data we’re gathering, working with international agencies like the Red Cross and Red Crescent, MSF and UNICEF is that this approach to using subconscious prompts has greater impact on behaviour.